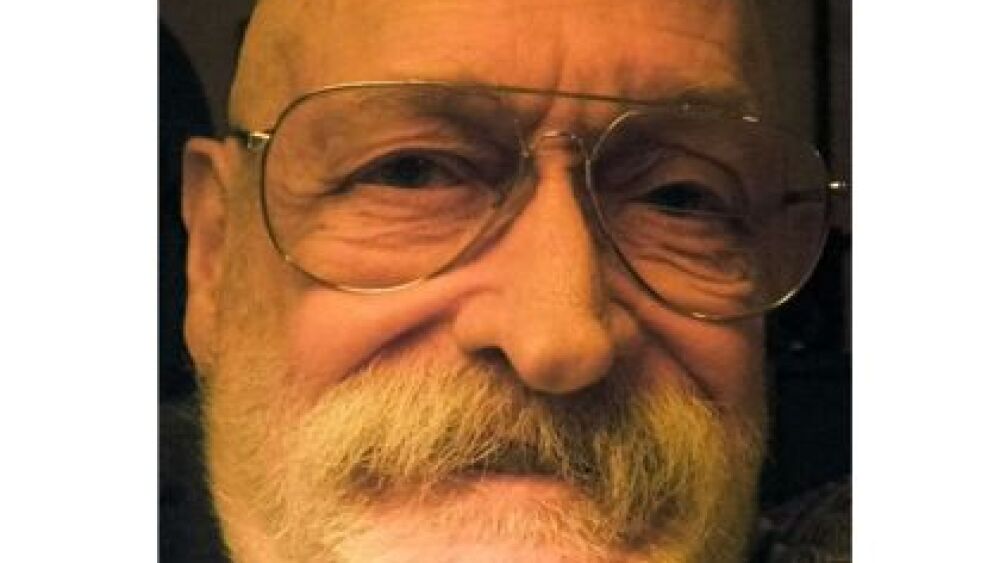

Texas EMS legend William E. “Gene” Gandy died peacefully at his home in Arizona on February 5, 2020. He was a medic, a scholar, a lawyer, a writer, a renowned teacher and an honorable man.

He was a dear friend, a colleague, and a collaborator of mine on many lectures and articles. He would not want us to mourn his passing, certainly not to pray for his soul, or to hope “he is in a better place.” He cared little for such sentiments.

Instead, he’d want us to be kinder to each other, to rededicate ourselves to being stewards of our profession, and to strive towards the scholarship, professionalism and compassion he thought every EMT should embody.

If you were one of the thousands he taught, mentored or influenced in some way strive to make EMS the better version he wanted it to be. Rest well, Gene Gandy. We’ve got it from here.

- Kelly Grayson, Paramedic, Educator, Author and EMS1 Advisory Board Member

Fifty miles northeast of Dallas sits Honey Grove, population 2,000 only if you round up. In 1975, EMS in Honey Grove was the responsibility of the local mortuary – not unusual at that time for small towns in the Lone Star State. When Honey Grove’s funeral director decided to concentrate on transporting the irreversibly dead, the city bought an ambulance, but didn’t have the money to staff it 24/7. That’s when Colorado attorney and Honey Grove native William “Gene” Gandy officially became an EMS pioneer.

“I’d moved back home to our family ranch, figuring I could practice small-town law,” Gandy says. “When the city had trouble running their ambulance, I met with the mayor and suggested we start a volunteer squad. I managed to find 35 people who felt the same, so we all got our first-aid certificates and formed the Honey Grove Volunteer Ambulance Service.”

Teaching EMS versus doing EMS

Soon afterward, Gandy and his pals heard about a new course called “Emergency Medical Technician,” with 10 times the training of basic first aid. Gandy got certified, then joined the faculty of Paris (Texas) Junior College’s EMT program, where he embraced the commitment needed to teach EMS effectively.

“You have to master the curriculum,” Gandy says. “You have to know the information backwards and forwards, in much greater depth than you thought you’d ever need as an EMS provider. That means you have to do an awful lot of supplemental reading.

“If you use one textbook to teach from, I don’t care how good it is, it’s still just one book. If you said you were going to get through medical school or even nursing school with one textbook, people would laugh at you, yet that’s how we teach our EMTs, AEMTs and paramedics.

“A good instructor has to go way above that. You need to look at the educational standards and make yourself an expert on every single point. Then you have to practice teaching. Hook onto somebody who can be a mentor who’ll let you break in gradually.”

From litigator to educator

In 1981, Gandy became a paramedic – the only one in Honey Grove – and continued to volunteer. “I was basically on call all the time,” he says. As EMS occupied more and more of his life, Gandy knew he was headed for a career change.

“I decided to become a full-time medic in 1989,” he recalls. “I’d been very involved in EMS at the state level: writing regulations and exam questions, serving on the Governor’s committee – things like that.

“I just didn’t like practicing law anymore. It’s a high-stress business. I was fortunate to have done well enough not to have to worry about income so I figured, what the hell, I’m going to do what I like to do.”

Gandy didn’t have to wait long for the right EMS opportunity. “I got a call that same year from the regional guy in the state EMS office. He said Tyler (Junior College) was looking to start a two-year paramedic program, and thought I ought to apply.

“Well, they picked me, and we built that program into something quite successful. The school still offers an Associate’s Degree in Emergency Medical Services Professions. I stayed there until I retired in 2004 and moved to Tucson (Arizona).”

Gandy says law school and his 25 years as an attorney taught him much more than the law. “You learn to think critically; how to gather and cull facts, then decide what’s important and what isn’t.

“One thing that seems to be a problem for EMS people is the difference between a fact and a conclusion. When you read most patient-care reports, they’re filled with unsupportable conclusions. For example, ‘Patient is A&Ox4.’ Well, that means they’re awake and alert to time, place, person and event, but how did you determine that? Lots of times, that awake-and-alert stuff is a conclusion with no basis. A good lawyer would rip that to shreds.”

What EMS providers think they know about the law

EMS workers often misunderstand legalities, according to Gandy. He cites the law of consent and refusal as an example.

“We don’t have to worry too much about consent,” he says, “because we can treat almost anyone under implied consent if we have to. Where we run into problems is when we either want to refuse a patient or the patient wants to refuse care against our advice.

“A refusal has some technical parts to it that are seldom taught to EMS students. You have to prove informed refusal, but before you get to that point, you have to prove your patient has the present mental capacity to understand the nature of his condition and the nature of refusal, and has enough mental acuity to make a rational judgment.”

Gandy says most EMS providers don’t know how to determine whether a patient has present mental capacity. Instead, they focus on mental competence – a legal concept rather than a medical one.

“Everyone is mentally competent unless they’re declared otherwise by a court. Even if you’re drunk, you may have lost present mental capacity, but that doesn’t mean you’re mentally incompetent. Failure to understand that difference can lead to poor documentation. I’ve seen very few written refusals that would stand up in court.”

Not the retiring type

Gandy wasn’t finished with EMS when he retired from Tyler Junior College in 2004. “I got a call from an instructor I’d hired at Tyler,” he says. “She was managing a rural EMS service in West Texas and asked if I’d like to come work for her. I ended up riding for Shackelford County EMS until 2007.

“Then I went back to Tucson with every intent of sitting by my pool and drinking martinis, but I got a call from a guy at Cochise College (about 80 miles southeast of Tucson). I ended up going down there and teaching for two years in their paramedic program.”

Today, Gandy works for Percom, an online provider of EMS courses. At 79, he still sees retirement as something others pursue, but he does make time for two of his non-EMS passions. “I’m hooked on mystery novels,” he says, “and I’m determined to find the best chile rellenos in southern Arizona.”