By Dan White

Courtesy photo Who are the ones you can’t see in this photo? Why, the EMS providers, of course! |

We are at the beginning of a safety revolution in EMS. For many years, safety issues have taken a backseat to the pressures of keeping the trucks rolling. But as we learn about the dangers our paramedics and EMTs face in the line of duty, it has become increasingly difficult to ignore the facts staring us in the face.

Simply stated, it is dangerous working in EMS. EMS professionals have about twice the national average of fatal injury rates while on the job, with the two major causes being run down while working on the roadway and ambulance accidents.

Inside the Ambulance

There are about 5,000 ambulance accidents each year, with one EMS employee being killed about every two weeks. These frightening statistics reveal the need for some creative problem solving and better workplace controls. One of the first mitigations pioneered to address this problem were improvements to driver training. EVOC training programs are designed to improve driver awareness and emergency techniques in order to reduce accidents and injury.

In 2006, the ANSI/ASSE Z15.1 Safe Practices for Motor Vehicle Operation received final ANSI approval. This new standard was intended to provide all fleet operators guidance about how to reduce commercial vehicle accidents. Unfortunately, the very design of the vehicles we use to transport patients dramatically increases our risks.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recently released videos of ambulance crash tests, and the results were frightening and revealing. Features like the squad bench and CPR seat are obvious sources of preventable injury. Dr. Nadine Levick has lectured around the country on the matter and has warned many about the risks of operating ambulances with passenger compartments that do not meet federal safety standards.

The fundamental problem is that our work environment is mobile and subject to the unforgiving laws of physics and mass. When we get into an accident, the attendant in the back is at extreme risk of injury from impacting against the wall or bulkhead if they aren’t buckled in. These risks are made much worse by interior designs driven by ambulance purchasing committees and not by safety engineers

There are many different approaches to reducing injuries from ambulance accidents. Several companies have pioneered advanced restraint systems for the attendant in the patient compartment. Paul Moore and Jim Green, of the NIOSH Division of Safety Research, have been testing some of these new mobile restraint systems, which are designed to move with you while you work.

And American Medical Response helped to pioneer the Ambulance Safety Concept Vehicle. This platform spurred on a creative surge from engineers and led to a number of design enhancements. One of the more simple enhancements is the idea of using chevron style stripes to enhance visibility.

Headgear

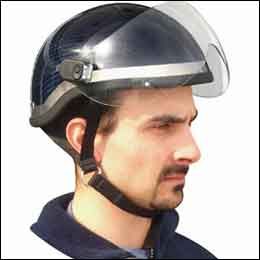

Another potential, yet still debated, concept is for EMS responders to wear helmets to reduce head injuries. AllMed just introduced the third generation AVC Helmet for EMS. The AVC Helmet, which I designed, is the first EMS helmet to meet Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. Many helmets often considered by EMS providers can actually be dangerous when worn inside the vehicle. The AVC Helmet is the only EMS helmet designed for use both when working inside the ambulance and while on the scene.

In February 2008, the National Fire Protection Association issued a revision of NFPA 1901, effective for apparatus contracted on and after January 1 this year. It states, “Fire helmets shall not be worn by persons riding in enclosed driving and crew areas. Fire helmets are not designed for crash protection and they will interfere with the protection provided by head rests The use of seat belts is essential to protecting fire fighters during driving.”

The problem is that firefighter-style helmets can cause more injuries than they prevent in a collision. The size and weight of these helmets, along with features like overhanging brims, oversized visors and hard mounted lights, all work to defeat vehicle safety measures like the headrest. For this reason, EMS providers should probably consider a different type of head protection than the ones that firefighters use.

Visibility

Being struck by a passing vehicle while working on the side of a roadway is another leading cause of fatality for EMS providers. Last November, the Federal Highway Administration established a policy for high-visibility safety apparel. These new regulations require the use of ANSI certified Class 2 or Class 3 garments by responders who are working within the right-of-ways of federal-aid highways. EMS agencies should have obtained these certified vests by now and be providing access to employees.

Another progressive approach to fulfilling this mandate is high-visibility outerwear, as seen in some of the new ANSI Class 3 certified duty coats and jackets from Gerber and Spiewak. The latest trends feature color-blocked designs with a more sophisticated style in an effort to make high-visibility apparel actually look good. I think the next logical step is to make our uniforms ANSI compliant as well.

Pathogen Protection

Courtesy photo The AVC Helmet by AllMed. |

Those in the EMS industry have spent billions on protection from pathogens. From safety needles to new expensive coats, we have focused huge resources on the protection from blood-borne pathogens. Yet, I’ve often wondered if the extra money spent on NFPA 1999-certified outwear actually reduces risks. The standard requires a specific style of construction for certified EMS coats, which is very expensive to produce. There has been no scientific validation to support the standard. But at least we now have much better choices for warmer and more weather-resistant duty coats.

However, we do know of proven methods to the reduce risk of coming into contact with blood-contaminated needles. The Smiths-Medical Advantiv Safety IV Catheter is one of the more recent developments in IV catheters. The Advantiv’s automatic sheathing needle protection is passive and does not require learning a new technique. Another notable product is the Stickit Sharps Container. While the Stickit is not new, it’s still one of my favorite devices for convenient point-of-use sharps disposal.

Conclusion

The very first safety product in EMS was the disposable glove. What started out as a policy to don gloves when exposed to blood or body fluids has today morphed into the practice of donning gloves while reroute to the scene. This was never the intent of universal precautions.

Today’s paramedic students are taught “Scene Safe, BSI” like it’s a protective mantra. I’m just not convinced repeating over and over again makes us any safer. What truly makes us safer is having a realistic appreciation of the real risks of our work and placing logical workplace controls. The products and processes that will help make us safer are mostly new. It will take time for our industry and manufacturers to respond to our needs with solutions that really work.

Some of those potential solutions are just now being realized. But it’s just the beginning, with a lot of important work yet to be done. For the very first time, we are finally learning the difference between what we think kills us and what really does kill us. This appreciation alone will help lead us toward solutions that will help reduce injuries and save lives.