By Doug Wyllie

EMS1 Staff

When the FCC’s wireless spectrum auction came to a close earlier this year, the plan to establish a public/private partnership — through which a robust, multi-purpose, national, interoperable, wireless broadband public safety network would be built — fell short of becoming a reality.

Finger-pointing and recriminations aside, the fact is that a much needed national interoperable communications network — conspicuously absent on 9/11 and again during the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005 — remains on hold more than decade since it was first proposed.

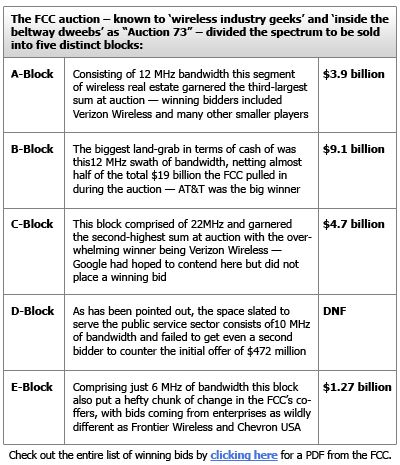

The reserve price for the so-called D-Block (wireless spectrum set aside for a national public safety broadband communications network) was $1.33 billion. Considering the fact that the FCC auction (which included four other “blocks”) was a wildly successful financial venture as it netted nearly $20 billion — nearly double the intended target — this doesn’t seem particularly high a price for assuring universal communications interoperability for the nation’s first responders. But the D-Block garnered just one bid ($472 million, rumored to be offered by Qualcomm) in the opening round of the auction, and after that, the airwaves both literally and figuratively went dead.

Both the private and public sectors are working to resolve the issue and it’s all but certain that a resolution will be carved out between the various interests — a group comprised of the FCC, NPTSC, PSST, APCO, IACP, DHS, wireless industry giants, technology industry titans, and others. But fundamental questions remain. How will the solution be structured; who will fund, build, and maintain it; and perhaps most notably, when it will be in operation?

Building the information autobahn

Little known fact: the Swiss and Austrian autobahn systems both require toll “stickers” and the German autobahn recently instituted a toll system for truckers seeking to use the ultra-fast road. The public/private national wireless broadband public safety network would effectively create a nationwide “information toll-road” on which commercial customers would pay for access to the mobile broadband network but would “pull over” to allow first responders to pass in times of emergency. Revenue raised in the collection of “tolls” would go to the ongoing improvements and upkeep that such a network would require.

Potentially at least, this is privatization in its most efficient, elegant form, and in theory would solve the massive problem of not just paying for the construction of the network — no small chunk of change, that — but also enable much faster upgrades to the communications systems than public safety entities use today. It’'s not atypical for major metropolitan forces (let alone smaller municipalities) to be operating communications gear reliant on decades-old technology. For all practical purposes, this new system would make that problem a thing of the past.

The plan, as it originally had been conceived, was to award a nationwide 10 megahertz commercial license in the upper 700 MHz “D-Block” to a winning private sector bidder, provided that aforementioned bidder enter into an FCC-approved Network Sharing Agreement (NSA) with the Public Safety Spectrum Trust Corporation (PSSTC).

This is bureaucrat-speak for: “We’ll license to you a nationwide swath of broadband on which you can build (and sell) valuable services, just as long as you give priority access to first responders in a time of critical need.”

The 10MHz of “space” that comprises the D-Block effectively would have been divided into two 5MHz segments —one devoted to public safety and the other set up for “paying customers” with a need for a high-speed national broadband (voice + data) network. These paying customers could include, but certainly not limited to, railroad companies, long-haul trucking concerns, passenger airlines, as well as national and international enterprises with large numbers of “mobile workers” who maintain their workplace in the nation’s hotels and convention centers. This premium would represent a significant source of revenue for the winning bidder.

No dice. The stakes proved just a shade too high for investors. Many feel that the rules and restrictions outlined in the auction became hurdles set too high to make the prospect an appealing business venture, despite the potential upside.

Changing the rules

Even before the auction began, many had said that the rules governing the auction of D-Block spectrum had preordained the outcome we’re now faced with. While the FCC is to be commended for doing something that government agencies fastidiously avoid — that is to say it tried something new and untested — we can in also say that the rules were certainly part of the problem, and rule changes are a must if the re-auction is to be successful.

|

Earlier this month, APCO suggested changes to the FCC rules that would significantly sweeten the pot for potential bidders by doubling the offer from a 10-megahertz block to be divided two ways to a 20-megahertz of spectrum to that which is already allocated to creating a public safety network. This idea may prove workable — it certainly makes the potential payoff for the winning bidder a lot more appealing.

Another idea that’s been floated is to remove the requirement that the network be coupled to a national licensee and instead create a set of technical specifications that regional bidders would have to meet. U.S. Cellular advocated this concept at the recent meeting of the principals from the FCC and the other parties concerned that was held in early August in Brooklyn, New York.

Under such an arrangement, the burden of the business “risk” would be shared more broadly — perhaps a half dozen or more companies would shoulder the cost and responsibility of building out the system rather than just one. This seems like an excellent idea, particularly from the standpoint of seeking to get the attention of the private sector, although many people in the public sector remain wary of the concept.

Still another solution is to simply reduce the asking price — many speculate that the original $1.3 billion reserve price was prohibitive — for the privilege of spending some unknown sum or money to build out the infrastructure. A different but nonetheless numerically-based answer could be to drop the required population coverage from its present mark of 99 percent to something along the lines of 93-94 percent, with the theory being that a truly serious mass casualty incident (other than a downed airplane) is less likely to happen in a very rural area not covered by the network than it is to happen in an urban area that is. Similar to this solution is an idea to extend the build-out deadline (the date by which the system would be operational) by five or ten years. Considering the fact that it’s been more than a decade since the national communications network was mandated by the Congress and Clinton administration, time may not be the best variable for negotiations.

Political remedy?

The prospect of a private/public partnership to solve this problem continues to have a great deal of appeal among people presently holding and/or seeking political office – and in case you hadn’'t noticed, there are several such folks getting a considerable amount of attention these days.

As recently as early July, presumptive Republican presidential candidate John McCain mentioned the need for a public safety broadband network at the National Sheriff’s Association Annual Conference. McCain last year sought to double the broadband capacity that the FCC set aside for public safety. The measure failed, and in point of fact was doomed from the outset, but the Republican surely will make an effort to help out the cause of the public safety broadband network from the “bully pulpit” should he win in November.

For his part, Senator Barack Obama, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, has spoken from the stump of the need for a national Chief Technology Officer who would hammer out the details of private/public partnership. This could prove an effective tactic since the CTO would have the bandwidth — pun intended — to get deep into the weeds on creating a framework solution with the FCC and other parties.

Regardless of who wins the Presidency, it’s abundantly clear that there will be a new regime in the White House and new faces in both the House and the Senate. Many of these people will bring to the Beltway a new energy and potentially even some new ideas — no guarantees on either front, but one can hope.

Lines of communication

FCC Chairman Kevin Martin recently indicated that the decision on whether to re-auction the 700 MHz D-Block spectrum could happen in September. September begins next week, and thus far, no news from Martin or the other Commissioners, let alone from the private sector.

Even in the pursuit of this article, there has been nothing from the private sector but radio silence regarding the public safety network. Various companies in the computer technology and wireless broadband sectors contacted by Police1 chose to "…not comment at this time…" or opted to not reply to our outreach at all.

Ralph Haller, Chairman of the National Public Safety Telecommunications Council (NPSTC) did reply to our request for comment and said in an email, “We are encouraged at the progress being made within the community to resolve the differences between some of our NPSTC members and look forward to a resolution so we can get the national broadband network built for our first responder community.”

Haller is talking about the fact that all the interested parties are talking. This is good because the viability of a public/private partnership for public safety communications interoperability and mobile broadband access will depend on these open lines of communication. Being hashed out are those lingering questions, like whether there be a re-auction in February 2009 as planned. If the re-auction happens, will licenses be made regional or will they remain national? Will the target build-out schedule stay at 10 years or jump to 15? Will the reserve price be lowered, and if so, to what level?

Most importantly, how can the FCC be sure that the rules it sets out for the re-auction will actually result in a winning bidder, and what will it do if no one steps to the table? Maybe the thing to which the FCC will revert —notwithstanding whatever happens in November in the House, Senate and White House races — will be to ask Congress to rewrite the rules governing the rule-writing such that the national public safety network can become a publicly-funded operation. After all, tax dollars pay for practically every other piece of public safety infrastructure.