A few weeks ago, I heard an annoyed EMS leader say, “Those 48-hour crews are killing us on no transports. When they are running calls on the second night of their 48, all they want to do is get back to bed, so they look for any excuse not to transport.”

He made this grand proclamation as if it were a fact engraved in stone. Only one person on his team, the QI officer, had the courage to challenge him. She said, “Chief, that’s an interesting theory. Do you have any evidence to back that up?”

An assertion is a confident or forceful statement of fact, whereas a theory is a supposition or idea intended to explain something with the understanding that it may not be correct or the whole story.

Theories are testable. It would be possible to pull the data on time of day and day of week when patients are seen but not transported, along with the shift schedule to determine whether or not 48-hour crews were the cause of the increase in non-transports. The results of this analysis would either support or refute the theory.

As leader of quality improvement thinking Edward Deming, Ph.D., said, “In God we trust, all others must bring data.”

Theory as invitation – The ‘I have a theory’ approach

As a leader, if you share your ideas about what’s going on as a theory, it invites the folks on your team to explore the issue with you. This approach inspires collaboration and teamwork.

When you say, “Our missed STEMI rate increased when we switched to the new electrodes,” it inspires your teammates to switch back to the old electrodes. If instead, you say, “I have a theory that our missed STEMI rate increased when we switched to the new electrodes,” or, “I wonder if the increase in missed STEMI is related to the new electrodes,” there is a better chance that your team will be inspired to improve your STEMI recognition rate and will look to see if the new electrodes are part of the problem while exploring other causes.

I have a theory that leaders who regularly use this “I have a theory” approach have more engaged teams, are more likely to have people tell them the truth about what they think, and produce better results. If you’re willing to try this approach out, please let me know how it works for you.

Theory and quality improvement

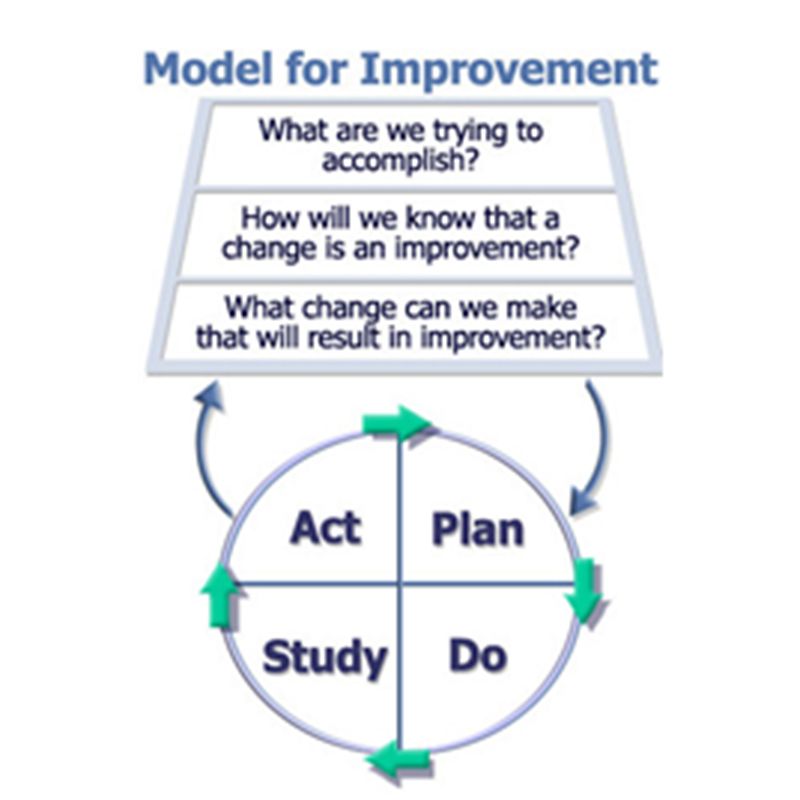

We’ve visited the Model for Improvement several times in this column.

Model for Improvement (Associates in Performance Improvement, Austin, Texas)

The third question, “What change can we make that will result in improvement?” is really a request for your change theories.

Recently, I was working with the QI manager for a multi-site ambulance service. Only 60 percent of their patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were getting aspirin or documentation that they were allergic to aspirin.

The manager had clarified what he was trying to accomplish: “Ensure that all of our patients with ACS received the full bundle of care as described by our medical director’s protocol.” His measurement system was in place: “What percentage of patients over 35 with cardiac chest pain received aspirin or documentation that they were allergic to aspirin, had a 12-lead acquired within 5 minutes of arriving at the patient’s side, were given nitro if their systolic blood pressure was over 110, had a final pain score that was less than their initial pain score, and had the cardiac intervention center notified early if the patient had a STEMI.”

When I asked him what he thought they could do to improve their performance, what I was asking for was a list of testable theories that could produce the results he was looking for. He said, “I will issue a memo this afternoon.” I replied, “Yes, you could do that. How has the memo strategy worked for you in the past?” He snorted loud enough that my office mate looked over from her desk. I pushed him, “What other ideas, in addition to a memo, do you have that might help?” Once he got rolling, a pretty good list emerged:

- We could hold a mandatory continuing education class on the topic.

- We could post infograms inside the stalls and over the urinals in all employee bathrooms.

- We could text a link to a YouTube video class on the subject to the rig smartphones.

- We could rubber band the aspirin bottle to the nitro bottle in the jump kit.

- We could duct tape an aspirin bottle to the 12-lead cable in the monitor.

- We could have dispatch encourage the patient to take an aspirin before the crew arrives.

- We could have dispatch remind crews of the need to administer aspirin as part of the dispatch information over the MDT.

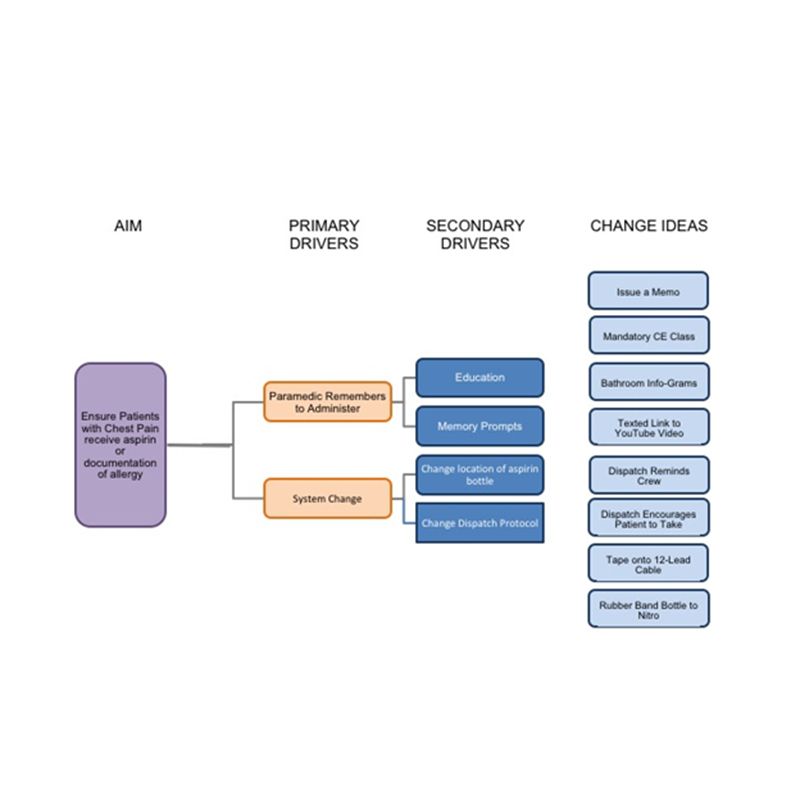

There’s a wonderful tool called a driver diagram that can help organize your change ideas (Figure 2). This is a flexible tool that’s designed to help you organize your testable theories and inspire creativity with your team. It’s a way to describe the path between your ideas and the outcome you’re hoping to create. I’ve found that the diagram itself is not nearly as valuable as the creative problem solving inspired by constructing it with your team.

Here’s a link to a template that makes these easy to construct

Sample EMS change idea diagram.

AIM/What are we trying to accomplish

Start crafting the diagram by writing down the result that you’re trying to create, your AIM statement.

For example: Ensure that patients with cardiac chest pain receive aspirin or documentation that they are allergic.

Primary Drivers

Beside the AIM statement, list the primary drivers or high-level categories of change that will likely contribute to improvement.

For example: A system that’s designed to support administration and paramedics who remember to administer the medication.

Secondary Drivers

Next, list the secondary drivers. These are the specific areas that drive toward the result you’re hoping to produce.

For example: These might include providing education to your crews, setting up memory prompts, changing the physical location of the aspirin bottle or changing the dispatch protocol so that call takers ask patients to take aspirin before paramedics arrive.

Change Ideas

Finally, list your change ideas. These are the concepts that might work to produce the desired result.

For example: These could include issuing a memo, providing mandatory continuing education classes, sticking infograms on the inside door of employee bathroom stalls, having dispatch remind the crew, etc.

Key points on the ‘I have a theory’ approach

The key points to maximizing the value of theory when it comes to performance improvement are:

- Remember that for most issues, there are many things that might result in improvement. The more ideas you have on your list, the more likely it is that you’ll find something that works.

- Sometimes activating more than one change idea produces a synergistic effect where the improvement is greater than any of the ideas would produce by themselves.

- Just because something should work or has worked in the past or worked for XYZ (pick your rock star EMS agency) does not mean it will work in your system.

- Brainstorm with the people on your team closest to the work. They will often come up with effective ideas that no one on the leadership team would ever think of.

- I have a theory that using the phrase, “I have a theory …” as a leader inspires teamwork much more effectively than issuing proclamations or assertions, even if you know you are right.