Editor’s Note: Recent acts of mass violence during active shooter events and other incidents in schools, churches and businesses continue to highlight the need for a multi-pronged strategy for both training and response.

This special EMS1/Lexipol guide outlines lessons identified from past incidents that can direct EMS involvement in pre-planning mass gatherings, improve multi-agency cooperation, and inform incident command and response strategies on the ground: Mass violence: How lessons identified inform training, response

The first 10 minutes of any MCI can make or break its outcome. Whether a multi-vehicle collision, natural disaster, or act of violence, training paramedics to establish command and a casualty collection point means triage can begin within moments of the first arrival on scene.

In preparation for a career in EMS leadership, I took advantage of as many incident command system (ICS) classes as I could. My resume was packed with letters and numbers like NIMS 300, USFA O-305 and Texas A&M - MGT 314. Upon promotion to EMS captain at The Richmond Ambulance Authority, I felt prepared to manage a large-scale incident but I made it my business to ensure the EMS providers in my charge had the training they needed to manage a mass casualty incident (MCI) as first arriving units on scene. I quickly realized I needed a training program (or tool) that allows providers to train on the first actions required at an MCI.

Taking MCI training to the table: Building NIMS City

When I was a U.S. Naval Sea Cadet, I spent time training with U.S Marines and their Navy Corpsman. Before any combat type training, the Marines would construct a sand table and play out scenarios using sticks and rocks to represent buildings and people. In my search to see if there was another public safety organization using sand tables or maps to preplan scenarios, I found the Phoenix Fire Department’s Command Training Center which used maps and projections to simulate emergencies.

The Phoenix Fire Department employed a collection of maps, miniature apparatus and tools to recreate disasters of all types. In the spirit of my 8th-grade shop teacher, I felt I could make better it myself. I started to evaluate what I would need to make this a reality. And I knew it had to be portable, non-locality specific, easy and fun to use. I needed a landscape or a large map for the scenarios to take place on. I thought about one of those rugs my kids used to play cars, the kind with the streets from a little city.

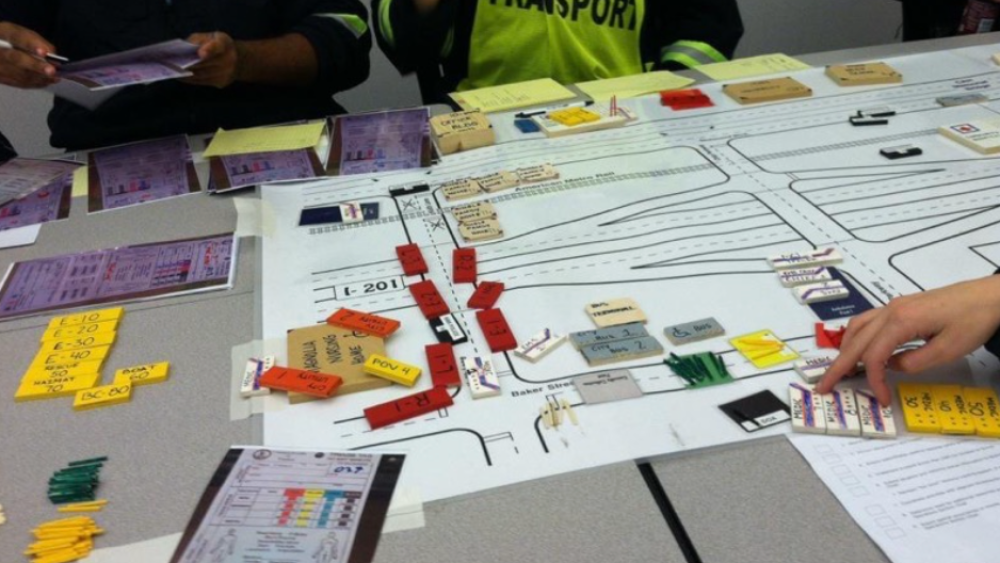

To keep it simple – and free – I hit up my dad, who is an architect by trade. He used a computer-aided drafting program to draw me a very simple map. I wanted it to be like Richmond, but not so much so that it couldn’t be used by someone who worked elsewhere. The map had neighborhood streets, a freeway and a river that cuts the city in half. It included an island with a port and a rail system that closed off major streets when a train was crossing (I pictured myself sitting cross-legged on Christmas morning making model trains shut down street that are preventing ambulances from returning to quarters after a late call). We called it NIMS City. The map was 8 feet by 4 feet and laminated, so we could write on it with grease pencils.

To make the simulations as realistic as possible, I needed to make buildings, apparatus and people. I went to my local craft store, looking for little buildings, but found something called “Bag-o-wood” and it had balsawood blocks of all sizes. I used these to make buildings like nursing homes, schools, houses and apartment complexes. Each block was painted with the title of what it was and its projected occupancy (i.e., single-family home or 20-unit apartment building). For the hospitals, I drilled holes in the front to represent bed capacity. I painted match sticks green, yellow, red and gray to simulate patients. I tried my best to find a large amount of toy emergency vehicles. I had all of my friends and coworkers raid their kids’ rooms for anything that could pass for a fire truck or ambulance. I just couldn’t find enough to equip the NIMS City Ambulance Authority and their NIMS City Public safety partners, so I made these units out of wood as well.

I even made a subset of vehicles from Outside County Fire & EMS. Each department had operation units, like ambulances or firetrucks, and there were command elements as well. When scenarios play out to include the mitigation phase, I included support assets like boats, mobile command centers, and MCI trailers. I included local and state law enforcement assets to include shift commanders and patrol units. This way, all of our public safety friends could play.

NIMS City now had fully staffed EMS, fire and police departments. I could get to work building scenarios. I created a master PowerPoint that described how the newly dubbed tabletop incident command simulator (TICS) worked. It included standardized staffing for each apparatus. I went into detail on how units would be moved from posting locations or stations to staging areas. I created four scenarios that described an event and then gave instructions to the players. They went from a six-patient car crash to a 30-patient MCI at a nursing home.

The scenarios include how many of each triage category each of the three hospitals in NIMS city can receive. Events include responder injures, news media requests or foul weather that threatens uninjured nursing home residents. We mirrored job aids and job action sheets that were located on the medic units and provided them to players who would have them if they were responding to an MCI.

Each scenario has triage tags that would be given to the EMS provider who would assume that role. These tags provide the information needed to complete START triage and the same worksheet located in the ambulances used to track the amount and type of patients. Once the patient’s triage category is identified, the participant places a matchstick in the casualty collection point and then moves it around the board to the treatment area, transport area, then “loads” it into a NIMS City ambulance and transports to a hospital.

When we have special events come up, we can create scenarios tailored to that event to identify stumbling blocks before they create stumbles. These could be anything from a car driving through a grandstand, to a train derailment or plane crash.

Rolling out an MCI training program

Once the TICS was loaded into its new handy dandy carrying case, it could be used, but how, and by who. I started by having all my peers in the RAA leadership team sit through a scenario. I felt like a kid presenting his vinegar volcano at the 5th-grade science fair, but it worked. And everyone seemed to enjoy it. Seasoned EMS leaders assumed the roles of triage officer or the first arriving medic unit and started wiping through triage tags with surgical precision. Before we knew it, all the patients were off the scene and the scenario was over.

I realized that the target audience may not have as much experience with START triage or MCI management. To compensate, I worked with my colleagues at RAA and they created a great set of PowerPoint slides on the topics. In preparation for our participation in the UCI 2015 World Cycle Championships hosted in Richmond, narrated versions of these PowerPoints even made it to YouTube for our non-RAA public safety partners to enjoy.

I started to present the TICS and accompanying PowerPoints to new providers during orientation. We would rotate FTOs and current employees through these NEOs so they could experience it as well. It took me a while to find my footing, but my third or fourth time presenting and running 10-20 medics through the program and scenarios, I found my groove. It fast became a top-rated event in the new employee orientation process.

Putting MCI practice into action

It was about 6 months after we began the TICS classes that I saw my first real sign of success. I had started getting paged to MCI response because of my role in TICS training. I responded to a bus crash with an estimated 20-plus patients. When I arrived, I found the paramedic on the ambulance had assumed command, established a casualty collection point, and his EMT partner was applying triage tape to all of the patients who could not walk. I felt like (insert famous athlete here) when they won (insert famous sports achievement here). I started to branch out, and give the presentations to paramedic programs, rescue squads and for peer committees at RAA.

When we responded to real-world MCIs we could pull out the TICS and use it to do real-time after actions, including radio traffic recordings.

We even found ourselves with public safety partners showing interest and sending their officers and firefighters to join us and explore their roles in scenarios. That fostered great working relationships with new medics and young officers who could someday find themselves responding to these types of scenarios.

The TICS became a valuable tool that is still used today, and could be adapted by any service for tabletop MCI training exercises.

Listen: Training hard and fighting easy

Brian Hupp joins podcast host Rob Lawrence, principal of Robert Lawrence Consulting and chair of the American Ambulance Association and a member of its media rapid response task force. Listen below as they discuss mass violence training and response.

| Read next: How to practice the EMS response to an MCI

This article, originally published in November 2020, has been updated.