This is article is the first in a series from the National EMS Management Association that will explore how principles of size and scale can be applied to EMS, while maintaining a strong community connection. This article introduces economies of scale. The second article describes how several large community organizations leverage their volunteer assets. The third article will explore how some innovative rural and volunteer EMS services, both domestic and international, have leveraged scale to their advantage.

By Sean Caffrey, NEMSMA

In the U.S. there are 21,283 transporting EMS organizations [1]. This number, while large, is not surprising considering U.S. Census Bureau figures reported that in 2012 there were 89,004 local governments of various types in the U.S [2].

Many local governments provide EMS directly or indirectly. Some of those services are independent jurisdictions or districts that provide EMS exclusively or in combination with other services.

The 2011 National EMS Assessment also found that a large number of EMS services are volunteer organizations with 16 states reporting that a majority of their EMS agencies were categorized as volunteer and another 16 states indicating that between 10 to 50 percent of the EMS services in their state were volunteer organizations. The data also suggests that many EMS services are rural, with 32 states reporting that a majority of their EMS services are rural [1].

Unlike many other countries, these figures clearly indicate the U.S. has a strong preference for emergency services that are provided and controlled at the community level. Many communities also operate EMS services separately from other government services such as law enforcement, fire protection or public works, which further drives up costs for infrastructure and administration [3,4].

This does, however, beg the question: Is this an efficient way to deliver EMS services? Especially considering the amount of duplication of administration and infrastructure that is necessary to run many small organizations that essentially do the same work.

Benefits of scale

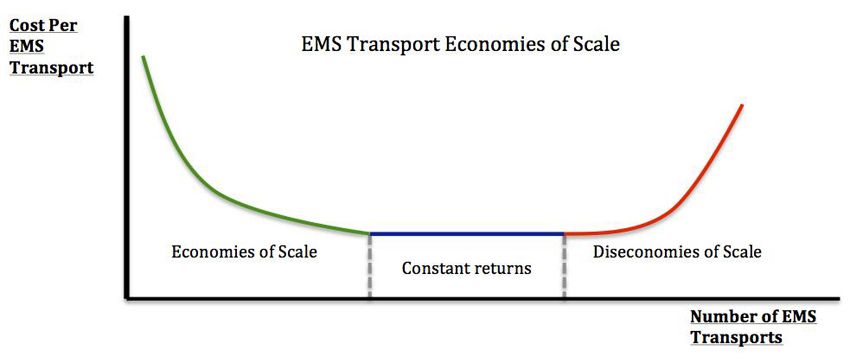

The concept of an economy of scale, at its most fundamental level, is that the average cost per unit of production will decrease as the number of units produced increases. The corresponding principle of diseconomy of scale suggests that as organizations grow larger they can develop or acquire inefficiencies that increase costs. This is shown graphically in this example that compares cost per transport to the total number of transports [5].

(Image courtesy Nathan Stanaway)

The economics therefore suggest that organizations should take advantage of size and scale to reduce costs, yet be wary of the inefficiencies that may also come with size. Economists have suggested that the primary benefits of scale include:

- Lowering input costs (volume discounts)

- Spreading the costs of expensive inputs

- Ability to acquire specialized personnel and equipment

- Improving organizational effectiveness

- Increased organizational learning

In the EMS context, larger organizations benefit from volume purchasing and the associated discounts that come with buying large amounts of oxygen, medical supplies, ambulances, fuel, uniforms and much more.

Costly items, such as software and communications centers, can be spread out more easily. Specialization further allows organizations to develop additional capacities in areas such as field supervision, specialty response capability, fleet maintenance, billing, human resources, public information and information technology.

Increased organizational effectiveness implies that large organizations develop more capable administrative structures and procedures to handle operations, finance, logistics and clinical quality. Increased organizational learning implies that more issues are bound to come up in a larger organization and the organization therefore benefits from learning how to address those issues over time as opposed to re-learning what to do each time.

Economies of scale: internal or external

Economies of scale can also be described as either internal or external. Internal economies are what an organization itself can do to reduce costs.

External economies of scale are generated from outside of the organization. For example, a tax-funded EMS system can spread the costs of the service across a larger tax payer base making EMS less expensive on a per-capita basis.

An external diseconomy might include serving an outlying or rural portion of a service area with a limited call volume. It is reasonable to assume that this type of diseconomy is why you don’t see a lot of private ambulance operators in rural areas.

EMS unit of production

Often the EMS unit of production is described as the availability of an ambulance to respond to a certain area. EMS provides emergency services to people and therefore is more efficient in areas with high-population density as this allows for more people to be protected by concentrated resources. Rural areas create the opposite situation where EMS resources must cover larger areas with fewer calls.

The most expensive aspect of EMS delivery is responders, which often account for 80 percent or more of the costs in paid organizations. Without an adequate call volume and a corresponding population density, it is often impossible for paid services to cover their costs with fee for service billing alone. In rural areas the use of volunteer personnel or the financing of EMS response through tax funding and other sources is needed as economies of scale diminish.

The question therefore becomes, how can scale be used by rural and volunteer organizations to best deploy paid and volunteer personnel, and what are good ways to save on administration, supplies and expensive infrastructure? And how can a strong connection to the community be maintained while also taking advantage of size and scale?

References

1. Mears G, Armstrong B, Fernandez AR, et al. 2011 National EMS Assessment. In: Administration USDoTNHTS, ed. Washington DC2012.

2. Bureau USC. Census Bureau Reports There Are 89,004 Local Governments in the United States. 2012; Accessed July 30, 2015.

3. Haynes HJG, Stein GP. US Fire Department Profile 2013. Quincy, MA2014. NFPA #USS07.

4. Reaves BA. Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, 2008. NCJ 233982 ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011.

5. Investopedia.com. Diseconomies of Scale. Accessed July 30, 2015.