By Rowan Callick

The Australian

Copyright 2008 The Australian

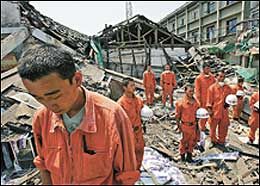

AP Photo A rescue crew in Tashui, China stands for three minutes’ silence. Officials report that more than 200 quake relief workers were killed by mudslides in the past three days. |

DUJIANGYAN, China — The rescue effort following last Monday’s devastating earthquake took a tragic turn yesterday when authorities revealed more than 200 relief workers had been buried by mudslides in southwestern China in the past three days.

As the number of people reported dead, buried or missing rose to 71,000 yesterday, China’s official news agency Xinhua said the workers had been killed by mudslides while repairing roads in Sichuan province.

An official at the Sichuan provincial Communications Department confirmed the mudslides but said: “The total death toll is still being counted.”

There have been numerous rockslides on unstable mountain slopes. Blocked rivers swollen by heavy rain have threatened to burst their banks.

As the country ground to a halt for three minutes’ silence to mourn the victims of last Monday’s quake, the number of people pulled alive from the rubble is dwindling to almost zero.

However, a 94-year-old man, Han You-ming, was rescued yesterday in the Sichuan hills at 8am (10am AEST). It took firefighters 10 hours to carry him across five ridges and valleys to bring him to the devastated town of Beichuan, where he was being treated last night at an army mobile clinic.

A doctor accompanying the man, who was still able to speak, said it appeared that he had strong life signs and appeared likely to make a recovery.

Two women were rescued yesterday after being trapped in the rubble of a collapsed building at a coalmine in Sichuan province. Workers were battling to free three other trapped people.

The military was struggling to reach cut-off areas, with more than 10,000 stranded in Yinxiui valley near the epicentre. There was no information on casualties there as 600 soldiers were hiking into the area.

The focus of relief efforts has switched to preventing further deaths — to keeping the 4.6million homeless survivors alive, by preventing outbreaks of infectious disease, finding them temporary housing and feeding and clothing them.

In an indication of the massive challenge China faces, the Foreign Ministry made an international appeal for tents.

“China requests the international community donate tents as a priority when they donate materials, because many houses were toppled in the quake and because it is the rainy season,” ministry spokesman Qin Gang said, also thanking the international community for its help.

The Government later announced China would allow in foreign medical relief teams.

The confirmed death toll from the quake rose to 34,073 late yesterday, although officials said the final figure was expected to pass 50,000, with more than 220,000 injured.

The biggest refugee camp is at Jiuzhou sports stadium on the outskirts of Mianyang city. About 30,000 people, including survivors from Beichuan, the worst-hit town, are camped around and inside the stadium, mostly sleeping on quilts laid on concrete.

Most will never return home. Xi Yingzhang, who was born in Beichuan, where he lost his 16-year-old daughter and his elder brother, said: “Beichuan is not a place to live any more.”

The road to the stadium from Chengdu, the Sichuan capital, was crowded with vehicles bearing red and yellow banners announcing their hearts had gone out to the quake victims. At one point, a convoy of 70 ambulances from Beijing swept past.

Around the stadium yesterday, volunteers from every province in China were providing free services to the refugees: young men from a beauty salon from Mianyang were cutting hair, and women from the psychology department of the South-West China University in Chongqing were providing counselling.

Volunteers from Guangdong were handing out bread buns, and workers from a fast-food firm in Mianyang were distributing rice and chicken soup to hundreds of people in a queue to register as disaster victims.

Many were wounded as they escaped the quake. Others queued at tents where medical volunteers were changing dressings and handing out medicine.

The grief and desperation of the survivors might be masked much of the time, but remains ever-present. On the walls of the stadium, faces stare desperately out from hand-made posters, a constant reminder of the disaster.

Twelve-year-old Cheng Bo, in the fifth grade at Liu Hai Hope primary school in Beichuan, was looking for his mother, father and 17-year-old brother. “Family members and anyone else with information, please call teacher Liu,” the posters urged, giving the teacher’s mobile phone number. Next to it, 10-year-old Mo Xiao-feng stared out forlornly from another poster. She was seeking her mother, father and 14-year-old brother. Teacher Liu was also waiting on her behalf.

The children were among about 300 being looked after in the heart of the stadium. They have all lost everyone close to them. They are only allowed outside to play twice a day, under careful supervision, and are being treated with special care.

Large numbers of people from around China are offering to adopt them, if their families do not emerge from the chaos.

Vehicles that enter Mianyang, a city of about 600,000 that is the main administrative centre of the worst-hit area, pass over sheets sprayed with disinfectant.

In tents outside the local relief command, there are tables spread with free phones, and members of the communist party’s Youth League are given their assignments as volunteers.

Red Cross teams are helping link relatives and friends with survivors.

“Our main concern is diseases spread by water, including cholera and diarrhoea” said Hou Zai-jin, who directs disease control efforts at the main command centre in Mianyang.

Many posters tell people to keep waste away from water sources, to bury dead animals deep, and not to share towels.