By Al Jones

Kalamazoo Gazette

Copyright 2007 Kalamazoo Gazette

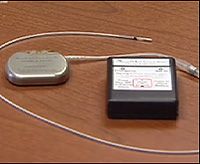

Photo courtesy of WBIR The Guardian aims at notifying a patient before the onset of heart failure. |

KALAMAZOO, Mich. — In late September, a small device implanted in the chest of a 55-year-old Brazilian woman makes a patterned series of buzzes.

Designed to monitor the electrical activity in her heart, the device warns her that she needs hospital treatment and then records heart activity that the machines she’s hooked up to later at a Sao Paolo hospital are unable to detect.

Using data collected by the device — a heart-attack early-warning system designed by Dr. Tim Fischell, of Kalamazoo — the woman, one of 20 test subjects for the product in Brazil, is hospitalized rather than released.

She is therefore in the hospital when she begins to have more severe symptoms. Doctors perform bypass surgery, sparing her a major heart attack.

Coming to market

Look for wide-scale, second-phase testing of Angel Medical Systems’ device, called the Guardian, during the first quarter of 2008, said Fischell, director of cardiovascular research at Borgess. If all goes well, he said, it will be launched for general use in less than three years.

“As many as three-quarters of patients who ultimately develop a large heart attack will have had some early-warning signs prior to the big event,’' he said.

“The hope here is to recognize (those signs) and alert the patient at the time of premonitory ascemic episodes.’'

In an ascemic episode, oxygen is not delivered properly to the heart.

The privately held Angel Medical Systems, founded three-and-a-half years ago by Fischell, his father and his brother and based in New Jersey, is entering its fourth round of funding for the Guardian to manage the next phase of testing. That will be Food and Drug Administration randomized clinical trials that may involve 1,200 test subject nationwide. To date, Fischell said, there have been seven test subjects in the U.S. along with the 20 in Brazil.

‘Time is muscle’

Congestive heart failure is the biggest expenditure for Medicare in the United States because people ignore or don’t recognize symptoms of heart failure and are slow to seek help, he said. It is not uncommon for people to attribute chest pains to indigestion: “I had chili last night — I thought it was indigestion,’' Fischell said as an example.

But not recognizing symptoms interferes with treatment Fischell said: “Time is muscle,’' he said Wednesday, referring to the loss of heart-muscle tissue while blood flow is stopped.

The Guardian, he said, “changes the paradigm.’'

“That average time from the onset of major heart-attack symptoms until a victim arrives at a hospital for help in the United States is about three hours,’' he said.

At least in part because of that delay, about one-third die before they get to hospitals, he said.

Closing the gap

In the United States, the average “door-to-balloon’’ time is 120 minutes. That’s the time between when a patient arrives at a hospital and he or she undergoes balloon catheterization, also called balloon angioplasty, to unblock a clogged artery. The door-to-balloon target is 90 minutes, Fischell said.

While he said hospitals are adept at helping people once they arrive, “We’ve never really had an effective intervention to deal with this major problem of `symptom-to-door’ time. We’ve never had very good success with getting them to come in.’'

The goal for the Guardian is to cut the time it takes patients to be convinced they need go to a hospital to one hour or less. It has the potential to get people to hospitals hours before heart attacks really start, he said.

While implanting and initiating the Guardian could cost $10,000 per patient, Fischell said, that is a radical reduction in what is typically hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs for treatment after a heart has been damaged.

He said he expects the Guardian to initially be recommended for people at high risk for heart attacks.