Editor’s note: The following is excerpted with permission from “The Little Ambulance War of Winchester County” by I.M. Aiken. About the novel: Following in the footsteps of their beloved Boston cop father, Alex Flynn trains as an EMT, and spends years chasing emergencies in ambulances. But the person Alex becomes is a far cry from the hero they signed up to be.

Over four decades in public safety (from the 1980s to the 2020s), Alex encounters a changing America, where veterans are left to rot on streets, women are welcome in dangerous fields but abusers still walk free, and service providers are subjected to intense public scrutiny while being denied the resources they need.

After moving from bustling Boston to small town Vermont, Alex discovers an escalating feud between emergency operators and must decide which to protect: their community, or their legacy.

In the near quiet of the driver’s seat, I reflected on the calls during the recent days riding with Aaron. Denny sent him, sent us, to calls related to veterans, regardless of where we posted in the city. It also meant that we got dispatched to calls involving street people. His hands and his recall of his time in Vietnam helped those who could barely be helped. Denny sent me to calls involving young people being victimized, abused, or just in the wrong place.

In four days, we earned a reputation as the hot rig. We sprinted from North Cambridge down to Kendal Square for a 111B. “26, Respond to Mr. Lincoln and his cane.” Mr. Lincoln was known to all crews. We told stories of how Mr. Lincoln swung his cane at people who were better off than him; or people who ignored him; or people who had paid attention to him. He stood in front of the big post office building threatening pedestrians and cars with his cane.

Mr. Lincoln, a Korean War vet, acknowledged Aaron as an army medic by using the honorific “Doc.”

Mr. Lincoln shared his remorse and shame with Aaron, “Doc, I am so sorry. I did it again, didn’t I? What are they going to do with me?” Aaron flashed me hand signs. “Stay,” “Ok,” then after getting Mr. Lincoln to sit on the granite curb, Aaron flashed me the hand sign for five with all four fingers and the thumb spread wide. I knew the plan. I fetched Aaron’s bag from between the seats. The five-sign stood for either “five” or “fifth,” we were never particularly clear on that. Aaron’s use of code “five” stepped beyond the boundaries of established, legal, protocols. It worked for Aaron. Even better, it worked for his patients.

I placed the bag between Aaron’s feet. Aaron lifted a pack of cigarettes and a Zippo lighter. He shook one free, offering it to Mr. Lincoln. He then flipped the lighter open, igniting the cigarette behind the cupped hand of a combat veteran. An army’s medical symbol, the caduceus, had been engraved into the stainless-steel Zippo plus the date: “1970.”

“Thanks, Doc.”

Aaron reached into his bag, where he had a plain Hershey’s chocolate bar. Aaron slowly unwrapped it, like a kid with a special treat. He moved deliberately while Mr. Lincoln puffed. He broke a piece off, eating it himself. He offered me a square, then carefully he offered Mr. Lincoln half of the bar. I sat on the curb next to Aaron. I’ll admit the smell of folks who lived on the street proved challenging for me. My nose curled away from Mr. Lincoln.

We were three friends, three veterans sitting on a curb sharing chocolate and a smoke. Except neither Aaron nor I ever smoked. Nor was I a veteran. Mr. Lincoln enjoyed the smoke, stubbing the butt into the same street where he once swung his cane at people walking by.

“My friend, you might want to find another corner today. I don’t think the PD needs to find you here today.” Aaron stood, offering the old man a firm grip to help lift him to his feet. Once up, Aaron handed over the last two gifts. I’d seen him do this before. Aaron placed a fifth of gin wrapped in a five-dollar bill into Mr. Lincoln’s hand. Aaron forged Mr. Lincoln’s signature on the ambulance run form. He forged the signature again on the “Against Medical Advice” release form.

The first time I helped Aaron with a “Code Five,” he said: “A drunk will die sober faster than he will die drunk.” Geez, man, if anyone went through Aaron’s bag during a shift, he’d get sacked in a second. You can’t carry booze on an ambulance. And nobody would ever recommend giving a patient a cigarette, at least not since World War II.

To Aaron, his “Code Five” protocol had everything he needed. Nicotine to calm, chocolate to bring up blood sugar, and booze to lift a soul one fifth of a gallon. I should add that I had previously looked in Aaron’s doctor bag. He carried a purple heart and his dog tags in there. He also had an old army shirt with rank, name tape, sweat stains, and a frayed neck collar. Aaron was always ready to treat and comfort one of his brothers. He spoke the right words and offered the right touch to bring peace with him, even if that peace meant passing a soul from his hands to Death’s hands. Peace is peace. We all find peace where peace is offered.

- Excerpted with permission from, “The Little Ambulance War of Winchester County” by I.M. Aiken.

- Published by Flare Books (2024).

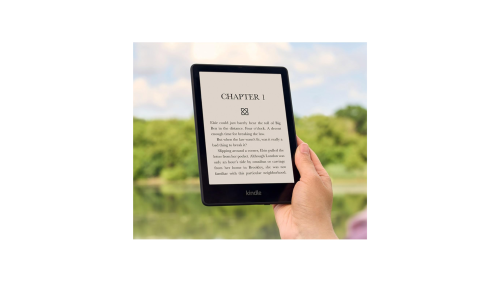

- Available from Flare Books and on Amazon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

IM. Aiken, who now lives in Vermont, worked on ambulances off and on since the 1980s, starting in the Boston area where she was born and raised. She also served one tour in Iraq as a civilian member of the U.S. Army’s 4th Infantry Division. “The Little Ambulance War of Winchester County” (2024) is part of The Trowbridge Vermont Series, which includes “Stolen Mountain” (2025) and “The Trowbridge Dispatch” (2025), a growing collection of short stories. All IM Aiken works are available as audiobooks, which she records herself in her home studio.