By Jean Ortiz

The Associated Press

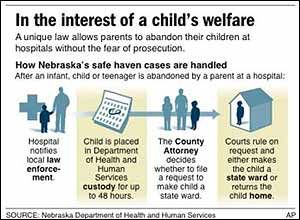

AP Photo This graphic shows how Neb. safe haven cases are handled once a child is dropped off at a hospital. State concerned of influx due to new law that doesn’t set age limits. |

OMAHA, Neb. — More than a dozen children have been abandoned under Nebraska’s unique safe-haven law, which allows children as old as 18 to be abandoned without fear of prosecution. But the case of a 14-year-old girl from Iowa has stoked fears of an influx of unwanted out-of-state children.

The law, which took effect in July, permits caregivers to leave children at hospitals. Like similar laws in other states, it was intended to protect infants. But the Nebraska law was written to include the word “child,” without setting an age limit.

Some have taken the word “child” in the law to mean “minor,” which in Nebraska includes anyone under the age of 19. Others have taken the common law definition, which includes those under age 14.

And the law doesn’t preclude people from out of state from leaving their children in Nebraska, which leaves some uncertainty about its current reach.

“It really concerns me that (people from) other states are possibly going to be leaving their children here,” said state Sen. Arnie Stuthman, who introduced the bill that was the basis for the safe-haven law.

So far, 17 children have been abandoned under the safe-haven law, including nine from a single family. A 14-year-old girl from Council Bluffs, Iowa, was left at a hospital across the Missouri River in Omaha late Tuesday.

Nebraska lawmakers aren’t scheduled to convene again until January, but they already are re-examining the law they passed in the spring.

Gov. Dave Heineman has not ruled out calling a rare special session of the Legislature to fix the law, but he has been reluctant to do so.

“The governor remains hopeful that a special session won’t be needed, but this issue must be addressed immediately at the beginning of the next session,” Heineman’s spokeswoman Jen Rae Hein said Wednesday.

Jeanne Atkinson, a spokeswoman for the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, said that despite the safe-haven law, the state could seek to press other charges, including child neglect charges, against those who abandon children.

Todd Landry, director of Nebraska’s Division of Children and Family Services, declined to say who left the child and under what circumstances, but said an investigation continues.

State Sen. Mike Flood, speaker of the Legislature, said that when the law is revised, he would like to see it pertain only to Nebraska residents, although he didn’t say how that might be accomplished.

Whoever abandoned the 14-year-old might be prosecuted in Iowa if a different law, such as child neglect, could be applied to the situation, Landry said.

Usually, when a criminal act is committed, its prosecution — or in this case absolution — is tied to the state in which the crime was committed, said Omaha attorney K.C. Engdahl, who has handled family law cases. But since this is a cross-border case involving children, that complicates the matter, he said.

“The state always has a reason to be involved when the best interest of minor children are implicated or involved in any way,” he said.

The number of children left will continue to climb, including the possibility of seeing children left by desperate parents pushed to the brink by the souring economy, said Kathy Bigsby Moore, executive director of Voices for Children in Nebraska. She pointed to research that links economic stress and other risk factors for children.

“My main hope is that this Iowa case doesn’t distract policy-makers from the real issue,” she said, “which is that Nebraska children and families need an avenue for obtaining services and respite for very difficult family situations.”