Editor’s note: Our Safety Leadership column is written by experts Michael Greene, Blair Bigham and Daniel Patterson. Following is part 11 of a 12-part series.

As Daniel Patterson likes to say, “Bad teamwork equals bad outcomes.” His statement is backed by research in aviation and other high-risk industries that depend on teammates working well together. But what does teamwork have to do with a safety management system (SMS)? Remember that the goal of SMS development is high reliability, in which organizations operate in environments where the consequences of errors are high yet the high reliability organization (HRO) achieves a low error rate.

Researchers and leading teamwork authorities Eduardo Salas, Ph.D., David Baker, Ph.D., and Rachel Day, Ph.D., argue that “Teamwork is an essential component of achieving high reliability, particularly in health care organizations.” In fact, the teamwork-outcome association, be it good or bad, is well documented in health care literature, quality assurance processes and, unfortunately, litigation.

Consider findings from a simulation study led by NASA in 1986 on flight crew familiarity among new and unfamiliar aviation crews:

-

More errors

-

Less speaking up

-

More social chatter, less work-related communication

Also consider a report from the National Transportation Safety Board that investigated commercial aviation accidents from 1978 to 1990. Findings show that in 11 of the 15 accidents for which data were available (73 percent), the accident occurred on the crew’s first day flying together; and in seven of 16 accidents (44 percent), the accident was the crew’s first flight together. First flight or first day, the percentage of accidents is greater than would be expected.

| Tuckman’s Team Cycle Model | |

| |

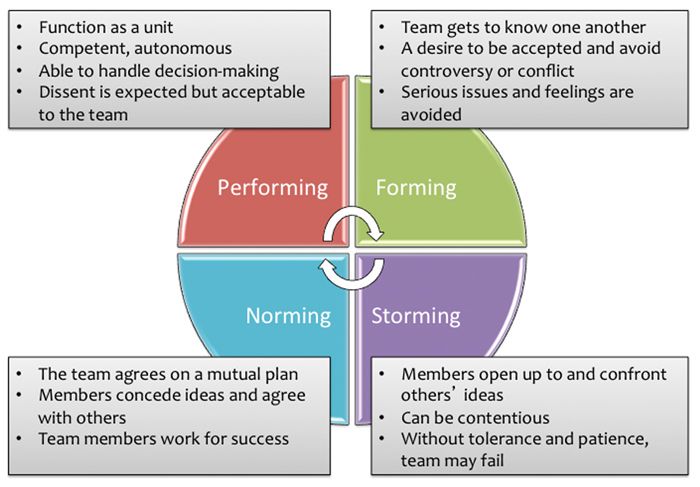

“Teamwork takes time,” Patterson says. “Just look at the widely known Team Cycle Model proposed by Bruce Tuckman in 1965.” As the model at right demonstrates, teams go through a series of phases: forming, storming, norming and performing. Patterson emphasizes that while not all types of teams go through each phase in a linear fashion, most (if not all) are a necessary and inevitable part of team development. Still unclear is the time frame—in hours, days or weeks—for a team to progress to the performing stage of the team cycle.

But where is the research on teamwork in emergency medical services? In one study of EMT partner familiarity, Patterson and his colleagues at the Emergency Medical Services Agency Research Network (EMSARN) found that within a study group of three agencies and 182 EMTs, the average EMT worked with 19 different partners annually. Some worked with more than 50 partners during a 12-month period! That’s a lot of partnerships and a lot of teamwork to develop. Given the expansive research from the aviation and health care industries, first day together/first run together may raise the risk for poor patient outcomes and safety.

The seven C’s of teamwork

According to Eduardo Salas, the key components of teamwork can be characterized as the “Seven C’s.” (For more on this, listen to the EMSARN podcast at emsarn.org.)

-

Communication The information protocols that team members use to complete the task. This includes frequency and accuracy of communication. This “C” can be developed through the use of structured communication such as SBAR (situation-background-assessment-recommendation) or protocols on “read-back” of critical communications.

-

Coordination A behavioral strategy or mechanism to execute a task. It includes back-up behavior and situation monitoring.

-

Cooperation The motivational aspect of teamwork in which a team member seeks input from other team members and enjoys the team.

-

Cognition The understanding and knowledge of the mission, task and equipment.

-

Conflict According to Salas, all teams have conflict—and some conflict is good. Conflict around the mission or task, not between individuals, may enhance teamwork.

-

Conditions Asserted and supported by the organization that values teamwork.

-

Coaching Effective team leaders coach teamwork through education and, most important, by their actions. According to Karl Weick and Kathleen Sutcliffe, authors of Managing the Unexpected, a key concept in coaching teamwork is deference to expertise rather than experts. They emphasize that expertise is relational and that knowledge, experience, learning and intuition is seldom embodied by a single individual. They write: “Expertise resides in the heed with which people view their inputs as contributions rather than as solidary acts, represent the system within which their contributions and those of others interlock to produce outcomes, and subordinate their contributions to the well-being of the system, constantly mindful of what that system needs to remain productive and resilient.” The lesson here: A great coach defers to the expertise in his or her team.

Salas emphasizes that in stressful emergency situations, three of the teamwork C’s matter the most: conditions, communication and coordination. Teamwork must be the organization’s goal and practiced by the individual team members. The team must have timely, clear and concise communication followed by the elements of coordination (i.e., situation monitoring and back-up behavior). He concludes that the most frequent disrupters or derailleurs of teamwork that are readily controlled by the organization are culture and mutual trust, reiterating that the conditions for teamwork must be established, coached and supported for teamwork to be successful.

So who has your organization’s back—and, ultimately, the employee’s and patient’s back? The answer is clear: You do. Through teamwork, safety and the tools we have provided, you can achieve a high reliability organization.

Michael Greene, R.N., MBA, MSHA, is a senior associate at Fitch & Associates. He has served in numerous front-line and leadership positions throughout his career, working in volunteer and paid search and rescue and as a paramedic, county EMS director and air medical/critical care transport director. He is the author of numerous articles and chapters on EMS and air medical transport topics. He can be reached via e-mail at mgreene@fitchassoc.com or by phone at 816-431-2600.

Daniel Patterson, Ph.D., EMT-B, is an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He is currently conducting a study on teamwork and conflict in EMS and regularly podcasts safety topics at EMSARN.org.