By Emilie Raguso

Berkeleyside

After a 63-year-old man collapsed and struggled to breathe it took paramedics from the Berkeley Fire Department 27 minutes to arrive because of a crowd of protests that numbered 800 strong, according to documents obtained under a Public Records Act request. The man later died.

For 23 of those minutes on December 7, 2014, paramedics were waiting for a police escort, as per a standing city protocol, to ensure they could avoid the protests and reach the man after he collapsed and struggled to breathe. On average the Berkeley Fire Department’s response time is 5.5 minutes.

Unusual occurrence reported to Alameda county EMS

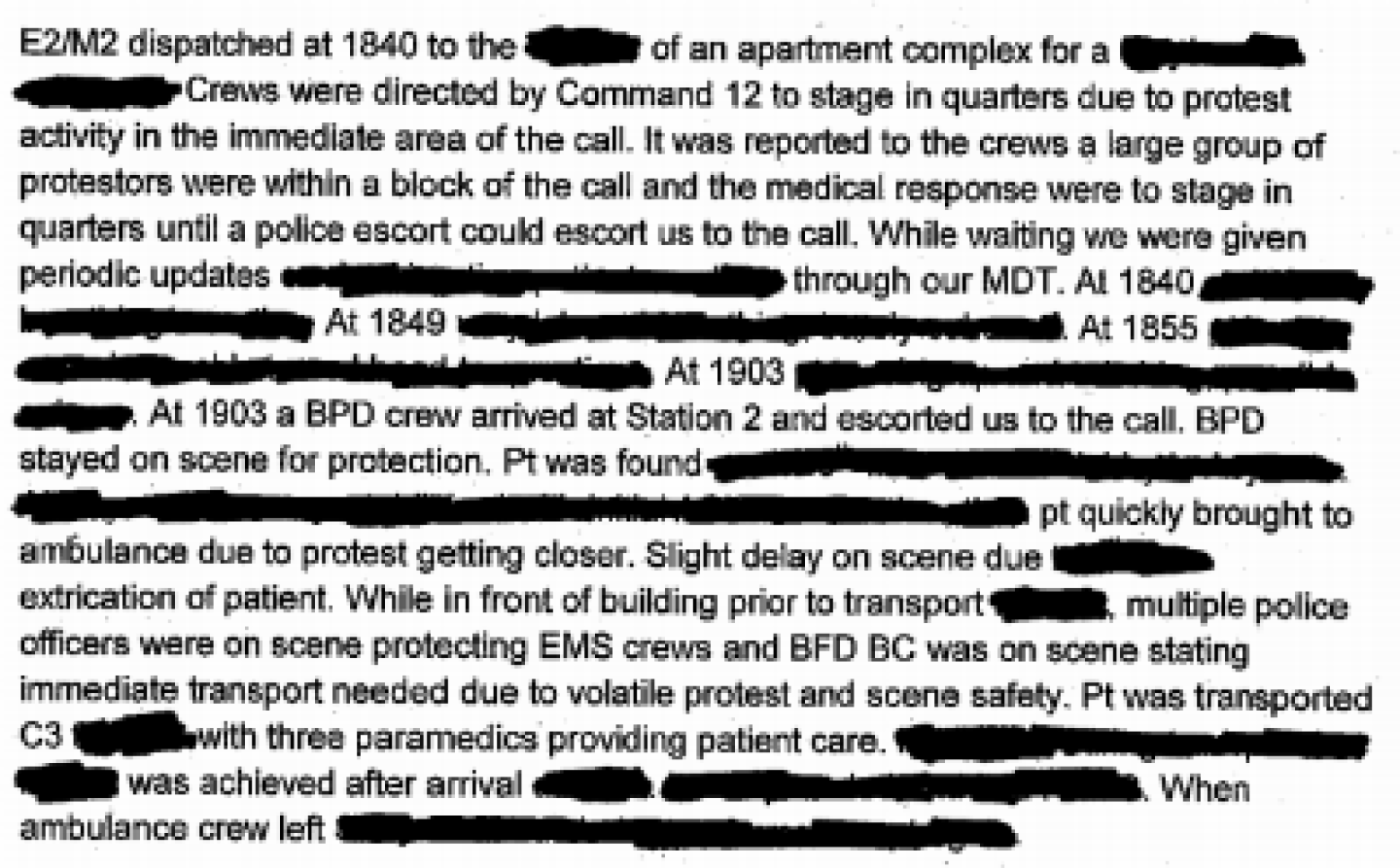

The response time was so delayed that a Berkeley paramedic was required by law to file an “Unusual Occurrence” form with Alameda County. Paramedic supervisor Rachel Valenzuela filed the form Dec. 9, less than two days after the Dec. 7 call on Kittredge. The form indicated that patient care had been affected during the call, and replied in the affirmative to the question of “Could this event cause a community reaction or represent a threat to public safety?”

Berkeley fire chief Gil Dong said Tuesday he could not clarify what “this event” referred to, but said the addendum to the form provided additional detail.

Nearly all medical information was redacted from the documents, but they did reveal that three paramedicsprovided advanced life support to the man during his 8-minute journey to the hospital, where he arrived about 52 minutes after dispatchers first received a 911 call about his condition.

The Alameda County coroner’s office identified the man Thursday as Alvin Henry Jones Jr., a 63-year-old Berkeley resident who died of natural causes. According to the coroner’s office, Jones died Dec. 9 at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Berkeley.

Addendum to the Unusual Occurrence form with parts redacted by the Berkeley Fire Department

DEC. 7: THE TIMELINE

6:39 p.m. Caller informs dispatch that paramedics are needed on Kittredge

6:40 p.m. Engine and medic are dispatched, but told to wait at the station for police

6:40 p.m., 6:49 p.m., 6:55 p.m., 7:03 p.m. Medical condition notes redacted

7:03 p.m. Police arrive at Berkeley Fire Station 2 (23 minutes elapsed)

7:05 p.m. Police and fire arrive at Kittredge (25 minutes elapsed)

7:07 p.m. Paramedics reach patient (27 minutes elapsed)

7:23 p.m. Paramedics and patient en route to hospital (43 minutes elapsed)

7:31 p.m. Paramedics arrive at hospital (52 minutes elapsed)

In the addendum, Valenzuela wrote that an engine and medic were dispatched at 6:40 p.m. to Kittredge Street — about a minute after the initial call — but were directed by a commander “to stage in quarters due to protest activity in the immediate area of the call. It was reported to the crews a large group of protestors were within a block of the call and the medical response were to stage in quarters until a police escort could escort us to the call.”

The team waited for police at Fire Station 2, at 2029 Berkeley Way, and received periodic updates on its computer system about the call, according to the addendum. At 6:46 p.m., according to another Berkeley Fire Department report that included a log with timestamps, the reporting party from Kittredge called dispatch again. Details about that call were redacted, as were other updates related to the man’s medical condition at 6:40 p.m., 6:49 p.m. and 7:03 p.m.

Berkeleyside reviewed scanner recordings to learn more about the incident. In those recordings, the man was identified as a 62-year-old who had collapsed on the fifth floor of 2175 Kittredge St. A fire dispatcher said the man was having “difficulty breathing, and sweating,” adding: “The subject will be in front of the elevator.”

Police arrived at 7:03 p.m. to Station 2, at 2029 Berkeley Way just west of Shattuck Avenue, according to the addendum. The police and firefighter team left for Oxford Plaza, a 97-unit affordable apartment complex on Kittredge, and arrived two minutes later, just before 7:05 p.m.

Paramedics went into the building, where they made contact with the patient at 7:07 p.m. Police officers “stayed on scene for protection,” according to the report. The patient was “quickly brought to the ambulance due to protest getting closer.” The supervisor wrote that there was a “slight delay on scene” related to the extrication of the patient, but no further detail was provided. (Dong said Tuesday he could not comment on the nature of the extrication due to medical privacy laws.) One source familiar with the call said paramedics had to revive the man at the scene before taking him to the hospital.

“While in front of building prior to transport [redacted], multiple police officers were on scene protecting EMS crews and BFD BC [Battalion Chief] was on scene stating immediate transport needed due to volatile protest and scene safety,” according to the addendum.

The man was taken to a local hospital at 7:23 p.m., with a “Code 3" status, meaning lights and sirens were used.Three paramedics provided advanced live support during the 8-minute trip, which ended at the hospital at 7:31 p.m., 52 minutes after the first call had come in about the man’s condition.

Several city workers aware of the case told Berkeleyside the man who was assisted by paramedics later died at the hospital, and was believed to have had a heart attack. There is no way to know whether the man might have survived had paramedics reached him sooner, given the amount of information that has been released, but prompt treatment has been shown to make a difference in the treatment of heart attacks.

According to the records reviewed by Berkeleyside, it took first responders about 27 minutes to reach the man, and another 16 minutes to get him into the ambulance to leave for the hospital. The Fire Department’s average response time is 5.5 minutes.

It’s not the first time local protests have been linked to a death in Berkeley. In 2013, the city of settled a lawsuitwith the family of Peter Cukor, a man who was attacked and killed outside his Berkeley Hills home in 2012, after authorities said they had waited to respond to the call — which initially was not categorized as an emergency — to ensure they had enough resources on hand to respond to protests in Oakland. The city admitted no fault in that matter, but agreed to change dispatching procedures as a result.

Some blame city policy, rather than protests, in man’s death

Fire Chief Dong said he could not release any details related to the man’s health, or ultimate health outcome, citing privacy laws covering medical records. Berkeleyside first reported the death in December after several city employees confirmed, under condition of anonymity, that the man died after emergency crews were delayed in reaching him due to protests in the city Dec. 7. Since then, the city’s Police Review Commission has pledged to look into the movement of emergency vehicles as part of an independent investigation into the police response to the protests.

Fire Chief: “We can’t predict whether or not it’s going to be peaceful”

Berkeley Fire Chief Dong said in December that longstanding department policies prohibit firefighters from entering active protest zones without police escorts. Those policies date back to the late 1980s and 90s, he said, when there were riots in People’s Park as well as other demonstrations in Berkeley following the Rodney King beating by police in Los Angeles.

Berkeleyside sought all available documents regarding the Dec. 7 medical call to Kittredge to look more closely at the timeline, as well as what role the protests reportedly played for first responders that night.

Dong told Berkeleyside in December that his department fielded 16 calls in and around areas overtaken by demonstrations in Berkeley from Dec. 6-8. Those calls saw “extended delayed response times” of 5-25 minutes due to the protests, either because ambulances were unable to get through streets blocked by crowds, or because police escorts were not immediately available because officers were busy with other demonstration-related duties.

Dong said this week that Berkeley’s protocol regarding when police escorts are needed is a standard approach that is widely used. He did not have a document citation immediately available, but said he would try to locate it.

“Police and firefighters have been killed and injured nationwide getting in to violent scenes,” Dong said Tuesday. “That’s why we’re cautious when we enter any scene, whether it’s an individual assault victim or a protest that is violent, with the potential for rock or bottle throwing … which we observed on Dec. 6, 7 and 8.”

Authorities said protesters threw projectiles at police, injuring officers, on Saturday night, Dec. 6. Members of the crowd also hurled items at police Sunday, Dec. 7, though police kept their distance from the demonstrationsthroughout most of the night.

“When there are protests, and there is movement of protests, we can’t predict whether or not it’s going to be peaceful,” said Dong. “Fire departments and firefighters are not immune from getting hurt or injured during protests.… We’ve seen the protests get violent, so we’re going to approach things cautiously and with safety for all responders and others involved at all times.”

Dong said there is a “standing protocol” that firefighters will not enter a scene until police determine it is safe if there is a potential for violence. He said it’s not a decision made on the fly.

“Dispatchers know to ask police, who advise when it’s safe to enter,” he said. “That’s passed on to the Berkeley Fire Department. We work with, and wait for, the law enforcement determination about when it’s safe to enter.”

Dong said the Fire Department does not track fatalities in the city and does not keep a record of wait times on calls for police escorts. He said, in addition, he could not speculate about how current police staffing numbers might be impacting those wait times.

“Generally, when we get calls that involve violence, the police department gets there pretty quick,” Dong said. “Response times are generally pretty fast when there’s violence or the potential for violence.”

Article first appeared in the Berkeleyside